Days at sea are some of the best days. We eat, we relax, we eat, we attend lectures, we eat, we compose blogs, we eat, Kathy gambles, we eat, Kathy does laundry, we eat, ... I'm sure you are beginning to see the pattern.

The winds and seas have eased since yesterday. Wind is north to northeast about 25. There is a significant swell from the NE, but we are riding it comfortably. This kind of motion makes for good sleeping. Weather is cool and overcast, but visibility is ok.

A Perfect Lecture Day at Sea

Ice Pilot Lecture

The highlight of this sea day was a lecture by Captain Ray Jordan, Ice Pilot.

A pilot is a person with specialized local knowledge, who boards the vessel temporarily to advise the Captain in specialized situations. Pilots usually assist with port navigation. For example, a harbor pilot boarded the Maasdam at the dock in Boston and advised the Captain out to the last channel buoy, after which he disembarked onto a Pilot Boat to go home to supper.

Capt. Jordan boarded at Woody Point to assist our ship captain, Captain van Schoonhovenin, in navigating the Maasdam through the ice fields around Greenland.

During the winter Captain Jordan assists ship captains to navigate the frozen St. Lawrence River. In summer he assists cruise ships, as well as commercial vessels navigating the Northwest Passage across northern Canada. It was fascinating to hear of the Northwest passage, which has only been navigable for the past two summers.

When at home in Montreal, Capt. Jordan works as a local harbor pilot. I desperately wish I had copies of Capt. Jordan’s ice slides, which were fantastic. I took some photos of the auditorium screen, but they are too fuzzy to share. To say nothing of copyright issues.

Captain Jordan, Ice Pilot

Captain Jordan told us that the two most important things to know for ice piloting are the ship, especially it’s maneuverability, and to know the ice. He informed us that our ship, the Maasdam, has an ice rating of 1D, the lowest rating for the Gulf of St. Lawrence & the western North Atlantic.

The Maasdam is very maneuverable, with side thrusters in the bow, and azipods astern. The azipod is a sort of outdrive, a primary propulsion system which can be swiveled 180 or 360 degrees, depending on the installation.

Azipod Being Installed in Maasdam Sistership Oosterdam

Photo Courtesy hollandamericablog.com

Sources of Ice Information

Capt. Jordan's first technical topic addressed the sources of information about ice conditions. He talked about the old days, when the ice pilot worked with information gained from talking with other nearby ships by radio, as well as what could be seen with his own eyes. This information was combined with the pilot’s knowledge of how ice drift is affected by wind and current. Captain Jordan quipped that the most direct course through an ice floe is usually a circle, around the outside of the floe.

Today things are very different. Ice charts are published daily by the US and Canadian Coast Guards, using information obtained from vessel sightings, from reconnaissance flights out of Gander, Newfoundland, and from satellite photos. Charts are distributed various ways. The most commonly used method today is the internet. The charts show colored patches indicating ice location, and an “egg”, which provides information about ice type and condition.

A Sample Canadian Ice Chart for the Davis Strait,

Shown by Capt. Jordan on the Maasdam Screen

Color Indicates Ice Coverage; See Link Below

“The Egg”, Showing Local or Regional Ice Conditions

Top Number indicates Tenths of Ice Coverage

Lower Numbers Indicate Ice Type & Thickness

See Link Below for Code Explanation

Despite all these new methods, the ice pilot still must be aware of weather and currents for the past 2 or 3 days, to estimate drift since the most recent data were gathered. We were told that drift is influenced mostly by current, and much less by wind. We were informed, for example, that most of the ice we saw two days ago, departing Nanortilik, is gone from today's charts; evidence that conditions change relatively quickly.

Sources and Types of Ice

There are two sources of ice. The first is glacial ice. The second is sea ice, which is frozen sea water. Sea ice can accumulate through multiple seasons to form large chunks of very hard ice. Information about the kind and size of ice is included in the lower portion of the “egg”. An excellent explanation of these ice codes may be found at the following link:

http://ice-glaces.ec.gc.ca/WsvPageDsp.cfm?ID=10433

Every glacier tour guide has his or her "lingo" for designating ice size. Captain Jordan, whom I would consider to be more authoritative than most tour guides, recognizes four names.

>Brash is the little stuff, that remains after rotten first year ice melts and sort of falls apart. Good for making martinis.

>Next up are growlers, which show about 1 meter of ice above the water.

>From 1 up to 5 meters showing is designated as a Bergy Bit.

>Above 5 meters (about 15 feet) is a full fledged iceberg.

We are told that the berg that sunk the Titanic was a bergy bit, not a full grown iceberg, as portrayed in the movies. The ice in the La Diamant photo, shown yesterday and reproduced below, is brash.

Brash Ice in the Prince Christian Sound

Iceberg Floating off the East Coast of Greenland

Ice coverage shown on the Coast Guard maps is stated as "tenths". An ice coverage of 5 is 5/10ths, or about 50%. This is the top number in the “egg”. A second number designates the type of ice. For example, a designation of "2/0 of 7" means 20% coverage with first year ice about 30 to 70 cm. thick (sorry for the SI units, but that's how French Canadian ice pilots talk). A third number designates the size of an ice flow. These are the secondary numbers in the “egg”.

Glacial icebergs are created at the toe of glaciers, where large chunks of glacial ice break off, or “calve”, and fall into the sea.

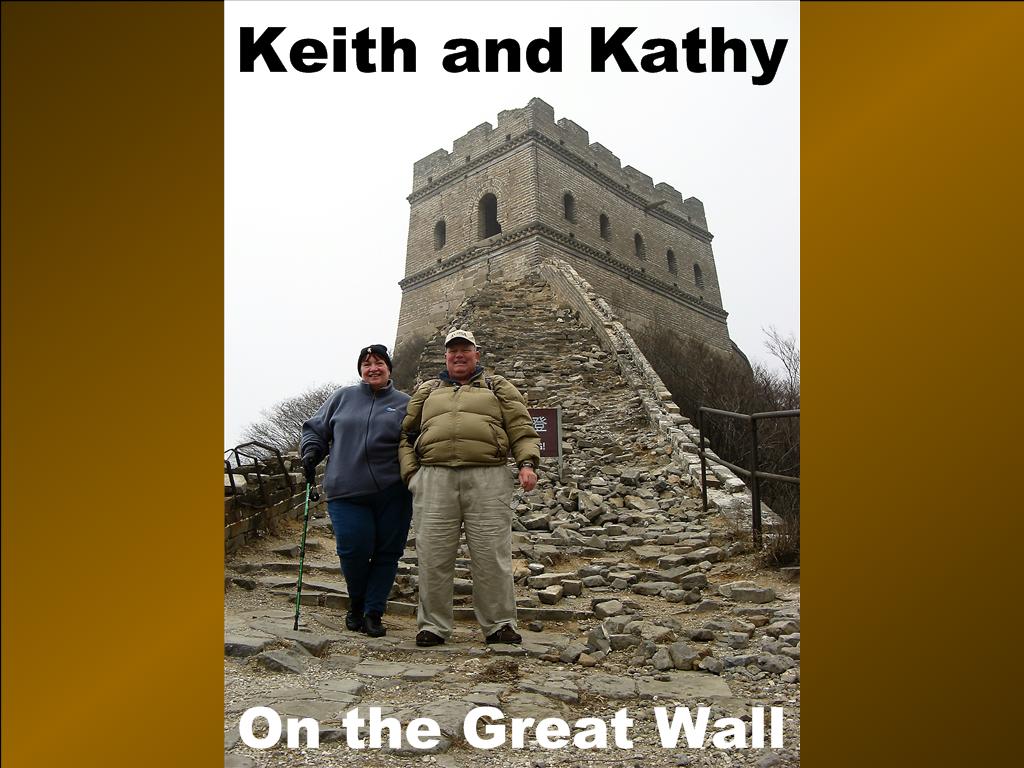

Iceberg Nursery, Photographed by K&K in Glacier Bay

Most Atlantic icebergs are generated in western Greenland, a large number in Disko Bay (also named Qegertarsuag), and many from a single ice flow named Jacob Sound Glacier. Some ‘bergs are created along the eastern coast of Greenland. Currents carry bergs south along the eastern coast, then north along the western coast of Greenland to the area of Baffin Bay, collecting fresh bergs from Disko Bay and other locations along the way. Ice is then carried south along the Baffin Island and Labrador coasts by the Labrador current, until it reaches the southern shores of Newfoundland, where most icebergs “die”, by melting. A few survivors are picked up by the Gulf Stream and travel east a bit before melting. This is the provenance of the bergy bit that sank the Titanic.

Most bergs die by melting from the bottom up. Older bergs show beachmarks many feet above the waterline, because the berg rises out of the water as the bottom melts. Some bergs have cris-crossing marks, showing the various depths and attitudes at which the berg has floated over the course of it’s life.

Bergy Bit With Multiple Beach Marks

Pockmarks at Left Indicate Incipient Deterioration of Sea Ice

Ice Navigation Hazards

Ice hazards take various forms, depending on the source of the ice. Icebergs float mostly underwater, with only a small fraction of their mass above the surface. Capt. Jordan says he can guess underwater shape from upper shape. Icebergs can and do capsize. We saw a small growler do so in Nanortilik harbor.

Clear Water Reveals Underwater Ice Extension

A Growler Floating in Nanortalik Harbor

The Above Growler Turns Turtle in the Maasdam’s Wake

Ice also forms directly on the surface of the sea. The danger of such sea ice depends on where it forms, and how long it lurks. New ice (first season) tends to be somewhat porous and soft, whereas ice that has been around for two or three seasons is much harder and more dangerous. Ice formed at the beach is very dangerous because it contains rocks and boulders. We were told that sea ice forms just above the water surface, where evaporated water freezes in the sub-zero air.

An Assortment of Ice Shapes

Iceberg or Bergy Bit?

Iceberg Swimming Pool

Captain Jordan considers growlers to be the most dangerous form of ice. They are large enough to seriously damage a ship moving at 17 knots (our current speed), but small enough to be difficult to spot, especially in high seas, fog, or darkness (all of which we have encountered in the past 24 hours). Growlers will show on radar, but can be very difficult to distinguish from sea clutter in high seas. Captain Jacob says fog is the worst condition to navigate ice. Dark (literally dirty) ice is also very bad, again because it is difficult to see. He indicates that if we were to hit a growler at our present speed, the bulbous bow on the Maasdam would be history.

Maasdam’s Vulnerable Bulbous Bow

Captain Jordan Photo of Dark Ice

The Human Variable

Captain Jacob also talked about ship captains. Some are easier to work with than others. Some will listen to the pilots' advice, and some are arrogant egomaniacs. He is very complimentary of our captain, and says he seems highly competent in general. Cynical Keith wonders how he could say anything else about his employer. Seriously, Keith is also impressed with Captain von Schoonhovenen

Towards the end of his presentation, Captain Jordan talked about his experience on the Saint Lawrence, and in the Northwest Passage. He showed many neat slides, which I wish I could reproduce here. So far, this lecture has been one of the more memorable parts of this voyage.

Tune in tomorrow for tomorrow’s memorable moments…

No comments:

Post a Comment